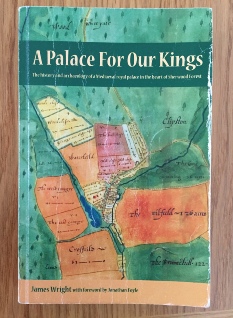

A Palace For Our Kings.

The history and archaeology of a Mediaeval royal palace in the heart of Sherwood Forest.

James Wright.

Triskelle Publishing.

The title of the book states that it is about the "history and archaeology of a Mediaeval royal palace in the heart of Sherwood Forest". The site to which this title refers is King John’s Palace in the village of King’s Clipstone in Nottinghamshire. The site is located approximately 6.5km northeast of Mansfield.

In medieval times, it was known as the King's Houses and was visited by all the Plantagenet monarchs from Henry II, who seems to have had the initial buildings constructed, through to Richard II (Crook 1976, p44). There was particularly extensive expenditure on the complex in the 13th – 14th centuries and there is a reasonable amount of contemporary documentation for the site, including lists of buildings standing on the site showing that by the 14th century it was quite a sprawling complex. It was not used by the Tudor monarchs and was described as being in ruin by 1525 (Colvin 1963).

Review

This book states that it is about the "history and archaeology of a Mediaeval royal palace in the heart of Sherwood Forest". The reader will be hard pressed to find much actual archaeology within its pages; there are for example no section drawings or photographs of excavated features, there is a single drawn plan (but not based on archaeological evidence), few artefacts are actually mentioned or discussed (those which are, are often wrongly interpreted or dated), and no drawings of any finds are present. These are all things that a reader might reasonably expect in a book about the archaeology of a royal palace (eg James and Robinson 1988). Indeed, the reader with some basic knowledge of archaeology will soon realise that this book contains many fundamental factual errors and misunderstandings.

The first chapter is poorly constructed and disjointed, consisting of a series of quotations from several key sources about palaces (Steane (2001, 1999), Keevill (2000), James (1990)) and general medieval history (primarily basic biographies of the key monarchs associated with the site) with no real attempt at tying them together into a narrative or coherent whole.

There is a heavy reliance throughout on royal biographies (Ormrod (2013), Barber (2014), and Warner (2014)) entry level texts with very little or no consultation of more specialist work. In fact, a quick visit to any reputable high street book shop and a flick through the indexes of the books on the Plantagenet kings which populate its shelves, with an eye for entries relating to Clipstone, will quickly allow any reader to assemble a very similar group of facts and quotations found in this book.

The second chapter consists of a confused and erroneous Prehistoric and Roman background. This chapter could have benefitted from the use of more up to date sources in order to allow a proper interpretation of the basic background of the archaeology of the area to be undertaken, or perhaps alternatively should have been omitted.

Following this somewhat shaky start by chapter 3 the book appears to begin to pick up, and at its best spins an engaging and lively historical yarn where the reader may be forgiven, due to the authoritative tone, for accepting what they find in this book as fact. This is where the danger lies, as many of the strongly stated 'facts' about the history and archaeology of Clipstone are seriously flawed.

For the most part supporting evidence is not presented and the reader is encouraged to accept statements about the site merely because the author states them to be so.

The book suffers from an incomplete discussion of previous and current work, instead focussing upon particular interpretations and ignoring sources that disagree with them.

Dating of the standing ruin

The method of argument throughout the book is to take a specific interpretation as fact, and proceed to build an argument by apparent logical progression. Unfortunately, the veracity of the initial interpretation is often flawed, these flaws becoming magnified by the subsequent argument, which conveniently ignores other perspectives.

A case in point is the assertion that the standing ruin at Clipstone dates from the 12th century and was built by Henry II as a direct copy of St Mary’s Guildhall in Lincoln (p33-

Henry II is known to have had a residence in Lincoln listed as an ‘Hospicium’ (Stocker 1991, p38). The Lincoln St Mary’s guildhall (situated in the former village of Wigford to the south of the medieval town), has been suggested by Stocker as the most likely candidate for Henry II’s Lincoln Hospicium (Stocker 1991, p38). Henry II held a crown-

The book tells an entertaining and vivid story of how, once Henry II had triumphed in the wars against his offspring (pp32-

The identification of the standing ruin at Clipstone as a replica of St Mary’s Guildhall has been examined in detail in Gaunt 2017 (with references), and is not included in full here. However, in short, regardless of whether the St Mary’s Guildhall was or was not the site of Henry II’s Hospicium, there are many reasons to question the suggested similarities between the Clipstone ruin, and St Mary’s Guildhall. The relative dimensions of the two buildings are not the same, the doors and windows are in different places and there are not the same number of each. It is not even definite that the gap in the ruin at Clipstone is the original main entrance to the building or that the supposed buttresses either side of this gap, on which much of the argument for the similarities between these two buildings rests, are the same. The decorative masonry found in a nearby garden and described in the book as being very similar to some at St Mary's Guildhall (p34) is in no way identical and, having been found at some distance from the ruin, could easily have come from another building on site, not the standing ruin. There are also walls extending from the ruin at Clipstone, and other entrances and structures integral to the building that cannot be paralleled at St Mary's Guildhall. These include two structures on the south-

With regard to any comparison of the two buildings it should be noted that Stocker actually states in his 1991 publication, that we should not expect to find a building like St. Mary’s Guildhall at a rural royal palace site such as Clarendon (Stocker 1991 p40). Clarendon is a site very similar in nature to Clipstone, and is the site most suitable to compare and contrast findings. If we would not expect to see such a building at Clarendon we should question strongly whether we should expect to see one at Clipstone.

Having excavated at Clipstone in the 1950s, Rahtz and Colvin dated the standing ruin to the 13th century (Rahtz 1960 p21 & p31), Colvin 1963 (p 919). Rahtz also suggested that there was evidence under the structure for two phases of stone buildings pre-

The book suggests that a recent re-

The pottery re-

Budge can clarify that the errors identified in Rahtz's dating were specifically a base from a Nottingham stoneware vessel that was correctly identified and dated but illustrated upside down, as a rim, in the report (Rahtz 1960, 43, no 11) and an unglazed inturned rim that had been marked "15th", presumably by the excavator and was in a small collection of sherds from the excavation given to the landowner and handed down with the field by its previous owners. This type of rim was revealed by work in the 1970s and 80s to be diagnostic of the late 12th -

Indeed, Sheppard’s 2016 report on the 1991 Trent and Peak excavations questions the re-

With the above points in mind, the assertions in the book about the origin of the ruin, the 12th century date of the ruin, the reasons for its construction, and any references to ‘crown wearings’ and the politics of the second half of the 12th century in relation to Clipstone (p33) must be seen as no more than speculation that is at present largely unsupported by any archaeological evidence.

Consideration of previous work

The reader may find themselves concerned by the book's criticism of the abilities and achievements of some of those who have previously worked at the site.

Most notably, we learn that the renowned architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner came to his conclusions, which the book questions (pp 100-

Howard Colvin, acknowledged in the book (in quoting Hewlings, 2008) as “the greatest architectural historian of his own time and perhaps ever” (p100), is, a page later, considered to have been wrong in his interpretations and conclusions regarding Clipstone due to the amount of work he had to do (p101).

Archaeological artefacts.

In addition to the dismissal of contradictory evidence, perhaps more worryingly, the book is littered with errors and factual inaccuracies when the focus turns to the archaeological evidence itself.

To cite just a few examples:

One of the few archaeological artefacts found on the site that is discussed in the book is an item identified as a 'mediaeval [sic] book clasp' (p17 and plate 6D). The item identified is actually a late 18th to early 20th century clog fastener (See Appendix I, section 1.1).

'Late Saxon shelly ware' is presented as archaeological evidence to support the argument for a mid-

A recently excavated figure of a stag on a fragment of Nottingham green glazed jug is actually looking forwards, not backwards over its shoulder as is erroneously stated in the book (p59). See Appendix I, 1.2 .

More details (with references) to these and other flaws in the basic data are presented in Appendix I.

With such basic and critical errors of dating and interpretation along with misleading statements about the majority of the included artefactual record (very few artefacts are actually discussed in this book which claims to be about archaeology), the reader would be entirely justified in having serious concerns about any of the conclusions that the book draws from such a flawed evidence base.

General archaeological and historical concepts and Terminology

These problems are, unfortunately, not just confined to the archaeology of Clipstone itself. The book features basic and serious errors of fact regarding medieval archaeology and history in general.

The book states (while referencing James and Gerrard 2007, 79, who certainly make no such claim) that "window glass ... was introduced during Henry's[III] reign" (p51). This is a surprising and distinctly radical statement given that some Roman buildings had glazed windows. Also, Salzman dates the re-

Saxon window glass has been excavated at Monkwearmouth and Jarrow (Tyne and Wear), Escomb (County Durham, Brixworth (Northamptonshire), Repton (Derbyshire), Flaxengate (Lincoln), Winchester (Hampshire) and other sites (Biddle and Hunter 1990, 350, 368-

In London Saxo-

Glass windows with painted figures were common enough that they were specifically banned from Cistercian houses in the Statutes of the Order (circa 1134) (Salzman 1952, 175). One should also not forget the many surviving windows of 12th century date still to be seen in various ecclesiastical buildings throughout the country, such as Dalbury church, Derbyshire (probably the earliest surviving and of ?late 11th century date (Crewe 1987, 17)), Cantebury Cathedral, York Minster and so on.

The book goes on to state that "Due to its fragility glass was probably manufactured close to the site whereas lead was brought in from the Peak District mines [in Derbyshire]" (p51). This is entirely contrary to the extensive documentary and archaeological evidence for the sources of window glass in the medieval period.

Coloured, along with the best quality white, window glass was made on the continent, in places including Burgandy, Lorraine, Flanders and Normandy, was shipped to ports in England and from there was transported by land and water around the country to be used in higher status building works (Salzman 1952, 183-

Not only was glass itself often transported long distances (glass from Shropshire and Staffordshire for instance was bought for glazing a chapel at Westminster (Willmott 2005, 46)), but even complete windows were sometimes transported from workshop to site of installation, for instance figures bought at Winchester and sent to Carisbrook Castle (Isle of Wight), or a series of windows made in Westminster and transported, at a cost of 4s (shipping -

Similarly, there are factual inaccuracies in the presentation of information about medieval pottery (see Appendix I, 2.1) and about the medieval diet (see Appendix I, 2.2), to name but a few other examples.

The book also contains medieval terms and historical terms which are used incorrectly.

For example, on page 94 the book mentions a horse harness pendant from Clipstone and describes riders "with copper alloy decorations fixed to the peytrell, the breast band, crupper and head ornaments" (pp94-

On page 33 the book refers to the ‘regnal year 1176-

Thus, the calendar year 1176AD would, in fact, be the regnal year 22 or 23, Henry II, depending on the month. The 1176-

Referencing

The more specialist reader wishing to follow up on some of the archaeology mentioned in the book (such as the aerial photographs claimed to show a possible earlier enclosure at Clipstone Peel site, p83) will be unable to do so due to the unsatisfactory referencing.

Some of the sources drawn from are fully credited and referenced in the text, footnotes and bibliography. However many; such as the aerial photograph, the finds of pot boiler stones of possible prehistoric, Roman or Anglo-

On occasion, there are references which are incorrect: an example of this is the reference given for the pottery sherd with a depiction of a stag (p59) mentioned above, referenced as King, C., (ed.), 2015, ‘Archaeology in Nottinghamshire’ in Transactions of the Thoroton Society Vol. 119. This article does not detail either the sherd itself or the archaeological work that discovered it. The article containing the reference to this pot sherd was actually Budge. D. 2016. Clipstone, King John’s Palace. In King. C, Archaeology in Nottinghamshire. Transactions of the Thoroton Society. Vol 120, pp16-

In the section on 'Assassin at Woodstock' that tells an exciting tale of an attempt on Henry III's life by a disgruntled clerk and its archaeological impact (p47), the book references Matthew Paris's 13th century account of the event and further provides references to the installation of iron bars in specific royal residences around this time documented in Salzman (1952), Steane (1993) and, relating specifically to Clipstone, Turner (1851).

Reading this passage, the reader may gain the impression the story was uncovered by the author. What is not made clear is that a similarly vivid description of the event is related by Steane (1999, p 99), with the re-

These references should not, however, necessarily be taken at face value as presented in the book. For example, in support of Henry's fear of assassination after the attempt, the book states "the plain glazed windows in the privy chamber were fitted with iron bars in 1238" (p47) and attributes this information to Salzman (1952).

What Salzman actually says is "Among the items of work to be done at Westminster Palace in 1238, a window of white glass was to be set in the iron-

Also concerning is the plagiarism of another worker’s theories. Though dwelling at length on the links between the Gawain and the Green Knight poem and the landscape of Clipstone, the book entirely fails to mention or reference that these ideas were developed and applied to the landscape of Clipstone by Gaunt (Gaunt 2011), whose work was itself inspired by Amanda Richardson's work at Clarendon (Richardson 2007). The book instead appears to present the theories as those of Wright, through the failure to ever suggest otherwise anywhere in the book.

The link of Romance literature to the design of the landscape of Clipstone was first suggested by Gaunt in 2011. A large portion of the content on the landscape analysis and interpretation within the book is directly or indirectly drawn from Gaunt’s work from 2011 which formed the basis for a publication in a joint paper (Gaunt & Wright 2013). Gaunt wrote the 2013 paper and included Wright’s name due to his contribution to elements regarding the built environment. The ideas relating to the designed landscape, romance elements and specifically the Gawain and Green Knight poem in relation to the landscape at Clipstone are those of Gaunt. Wright’s contribution to previous work at Clipstone was not in relation to the landscape. The book does not credit Gaunt for the theories regarding design or romance.

Instead, in the book’s preface, writing in the first person, Wright claims to have been directly inspired by both the 1630 map and the Gawain and the Green Knight poem to undertake his research (pp vi-

Interpretation of the built environment

Due to the way it is presented, the reader may also be misled by the scale plan of the complex of palace buildings on the site on page ix. The map appears to show the location of the Great Hall, Pentices, Privies, the Kings Kitchen, Queen’s Kitchen, Queens Hall, Rosamund’s Chamber, King’s and Queen’s Chambers, Kitchen, Buttery, Pantry, Porch, Chambers, and Roger de Mauley’s Chamber… to scale on a measured plan. To date there is no archaeological evidence to support the positions, size or use of these buildings. Strangely, while the layout and dimensions of these named buildings are shown in detail, the standing ruin and excavated or geophysical features that are known are neither given a reconstructed floor plan or, for the most part, assigned a function or name. Where archaeological evidence or anomalies are shown on the map, they do not have any function or interpretation provided, and are listed simply as “excavated and geophysical anomalies”. The only buildings that are mapped that are based upon archaeological evidence are a ‘tower?’ (Rahtz 1960), and a ‘chapel?’, mapped as relating to the rectangular building found and partially excavated by Wessex (2011). The Gatehouse is the only other feature from archaeological work that in reality has a known (or measured) location. The standing ruin is named ‘King John’s Palace’ on the map and in the text (p 103), even though it certainly did not carry this name at the time that the map claims to depict. No other building from the list above, (all of which are drawn on the ground as a measured plan), are suggested by archaeological evidence.

This is not normal archaeological practice, especially on a site of such significance. The use of historic documents cited in the book as enabling the reconstruction could have been useful if the author had provided a transcription and translation of the documents.

If the plan was derived primarily from these documents, as appears to be the case, the work could have been useful if interpretation had been limited to the creation of a schematic diagram depicting ‘this is next to this’ with referencing, degrees of certainty, and other caveats attached. This of course should not have been set in a “real world” cartographic map, but could have existed in isolation as a diagram or sketch. Such an approach would have been useful to researchers to determine possible uses and names of buildings if, and when, they are detected in either future archaeological prospection, or through excavation and would have been much less misleading for the general reader.

The drawing of outlines of buildings on a measured scale plan to give the impression that their locations, dimensions and functions are known, without any actual evidence of their location from any form of archaeological investigation is reckless and will mislead the reader, presenting an untrue picture of the state of knowledge about the site.

Worse still, it could be harmful to the protection and stewardship of the site: by producing a fictitious map purporting to show the extent of the built environment it is possible that planning authorities may grant permission for development on parts of the site where no buildings are shown on the map but which in actuality may contain significant archaeological remains, or that damaging and unsuitable cultivation activities, tree planting or other disturbance might be undertaken over parts of the palace site in areas that the map suggests are 'clear' of archaeology.

Summary

At its best, the book tells engaging and enjoyable tales of the kings and other historical people who can be connected to the site. However, it is presented as a serious academic study and written with an authoritative tone. Due to this, the reader may be forgiven if they come away with the impression that what they have read represents established fact.

The confident and forceful presentation of often unsubstantiated theory and supposition as fact, is a major drawback to this book. More serious still, are the deep and fundamental flaws apparent in the evidence base. When it comes to archaeology, either that of the site itself, or more generally regarding the medieval period as a whole, the book contains frequent and repeated errors, which presents to the reader misinformation regarding even some of the most basic concepts and terminology of medieval archaeology and history.

When such fundamental flaws exist in the evidence base, the reader can have little confidence in any conclusions reached from them.

Wright’s ‘A Palace for our Kings’, could be said to represent an alarming ‘post truth’ archaeology, written for a ‘post truth’ age, and the old adage 'never let the facts stand in the way of a good story', at times, seems particularly appropriate here.

It is essential in a book that presents itself as a factual and academic study that archaeological works are presented honestly, without exaggeration or falsification. Theories should be based on evidence, and that evidence should be presented to enable a balanced assessment of the arguments. The book unfortunately exaggerates the level of understanding of the archaeology of the site, and on occasion presents the work of others as having been undertaken by the author.

The book contains a lack of evidence for much that is stated, and where evidence contradicts the presented theories, the reputations of the archaeologists who have undertaken it are often called into question, or their evidence is simply ignored. The reader should be extremely cautious about accepting anything they read within it as fact without checking other sources, including checking that those referenced in the book actually support what they are presented as supporting.

Overall, ‘A Palace for our Kings’ has the potential to damage and harm the understanding of this nationally important medieval site in Sherwood Forest. It is likely to mislead its readers through the many factual inaccuracies in the evidence base, its misinterpretations and misrepresentations of the site, and its misrepresentation of medieval history and archaeology.

Wright suggests in his colourful epilogue that the purpose of this book “is to round up the sum of knowledge and research as it stands at the date of publication in the summer of 2016” (p 189). Unfortunately, ‘A Palace for our Kings’ comes in no way close to fulfilling its author’s stated purpose. Indeed, for the reasons stated above, and particularly for the harm that this book can do to the understanding of this site, we are unable to recommend James Wright’s ‘A Palace for Our Kings' to anyone.

Mercian Archaeological Services CIC.

September 2017

Ashley, S. 2002. Medieval Armorial Horse Furniture in Norfolk. East Anglian Archaeology 101. Dereham.

Barber, R. 2014. Edward III and the Triumph of England. Penguin Books.

Biddle M and Hunter, J. 1990. Early Medieval Window Glass. In M Biddle (ed) Object and Economy in Medieval Winchester, Winchester Studies 7. Oxford. 350-

Brennan, N. 2016. A Time Team Evaluation at King John's Palace, Clipstone: A Medieval Royal Palace Sherwood Forest. Transactions of the Thoroton Society of Nottinghamshire Vol 120, 45-

Budge, D, in prep, A Proto-

Budge, D. 2016. Clipstone, King John’s Palace . In King, C. (ed.) Archaeology in Nottinghamshire 2016. Transactions of the Thoroton Society. Vol 120.

Budge, D J. 2014. Clipstone, King John's Palace. In: Challis, K, (ed), Archaeology in Nottinghamshire 2014. Transactions of the Thoroton Society of Nottinghamshire 118, pp 1-

Colvin, H. (Ed.). 1963. The History of the Kings Works, Volume II, The Middle Ages. Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

Colvin. 1960. The Historical Background. Rahtz, P. 1960. King John's Palace, Clipstone. Transactions of the Thoroton Society of Nottinghamshire Vol. 64

Crewe, S .1987. Stained Glass in England 1180-

Crook, D. 1976. Clipstone Park and Peel. Transactions of the Thoroton Society, Vol LXXX.

Egan, G. 2010. The Medieval Household. Daily Living c.1150-

Egan, G and Pritchard, F. 2002. Dress Accessories 1150-

Gaunt, A. 2017. Geophysical Magnetometer Survey of King John’s Palace in Sherwood Forest. Castle Field, Waterfield Farm, Kings Clipstone, Nottinghamshire. Geophysical Survey Report MAS024, Mercian Archaeological Services CIC.

Gaunt, A, 2011. Clipstone Park and the King’s Houses: Reconstructing and interpreting a medieval landscape through non-

Gaunt, A., & Wright, J. 2013. A romantic royal retreat, and an idealised forest in miniature: The designed landscape of medieval Clipstone, at the heart of Sherwood Forest. Transactions of the Thoroton Society Vol. 117.

Hewlings, R. 2008. Sir Howard Colvin: Architectural Historian whose bibliographical dictionaries laid a foundation for all other scholars in his field. In The Independent, Tuesday 01 January 2008.

James, T.B. 1990. The Palaces of Medieval England. Selby. London.

James, T B and Gerrard, C. 2007. Clarendon Landscape of Kings. Macclesfield. Windgatherer Press.

James, T.B. & Robinson, A.M. 1988. Clarendon Palace: A History and Archaeology of a Medieval Palace and Hunting Lodge near Salisbury, Wiltshire. Reports of the Research Committee of The Society of Antiquaries of London, No. XLV.

Keevil, G. G. 2000. Medieval Palaces – an Archaeology. Tempus. Stroud.

McCarthy, M R and Brooks, C M. 1988. Medieval Pottery in Britain AD900-

Ormrod, W. M. 2013. Edward III. Yale University Press.

Rahtz, P. 1960. King John's Palace, Clipstone. Transactions of the Thoroton Society of Nottinghamshire Vol. 64

Richardson, A. 2007. ‘The King’s Chief Delights’: A Landscape Approach to the Royal Parks of Post-

Salzman, L F. 1952. Building in England Down to 1540. A Documentary History. Oxford. Oxford University Press.

Sheppard, R. 2016. King John’s Palace, April 1991 Excavations. York Archaeological Trust.

Stocker, D. 1991. St Mary’s Guildhall, Lincoln. The Survey and Excavation of a Medieval Building Complex. Council for British Archaeology for Lincoln City Archaeology Unit.

Steane. J. 2001. The Archaeology of Power. Tempus. Stroud.

Steane. J. 1999. The Archaeology of the Medieval English Monarchy. Routledge. London.

Warner, K. 2014. Edward II-

Warton, T. 1775. The History of English Poetry, from the Close of the Eleventh to the Commencement of the Eighteenth Century: To which are Prefixed Two Dissertations. I. On the Origin of Romantic Fiction in Europe. II. On the Introduction of Learning into England. Volume 1. London and Oxford.

Wessex Archaeology. 2011. King John's Palace, Clipstone, Nottinghamshire -

Willmott, H. 2005. A History of English Glassmaking AD43-

Wood, R. 2005. What did Medieval people eat from? In, Medieval Ceramics 29. 19-

Young, J, in prep, An Analysis of Pottery from Clipstone Excavated by Rahtz (1950s), Trent and Peak Archaeology (1991) and Wessex Archaeology (2011).

1. Archaeological artefacts.

In addition to the dismissal of contradictory evidence, perhaps more worryingly, the book which is littered with errors and factual inaccuracies, when the focus turns to the archaeological evidence itself.

To cite just a few examples:

1.1 ‘Book clasps’.

One of the few archaeological artefacts found on the site discussed in the book is an item identified as a 'mediaeval [sic] book clasp' (p17 and plate 6D). “During the later 14th century we have evidence that courtiers enjoyed reading aloud from texts to one another, and two book clasps discovered in 2011 point towards expensive hand-

The item identified as a ‘mediaeval book clasp’ (plate 6D) is actually a late 18th to early 20th century clog fastener. Clog or shoe clasps are common metal detector finds and there are many on the Portable Antiquities Scheme database, such as YORYM-

The book confuses whether these clog fasteners were found in 2011 (p17) or 2012 (p109).

It should also be pointed out that the location of gardens at Clipstone is not known and there is also no evidence to indicate that Chaucer ever visited the site, though as the book essentially points out, there is no evidence that Chaucer did not visit the site.

1.2 Saxon and Medieval Pottery

What the book describes as 'late Saxon shelly ware', quoted in support of the argument for a mid-

Additionally, the recently excavated figure of a stag on a fragment of Nottingham green glazed jug is actually looking forwards, not backwards over its shoulder as Wright states (p59) (Budge 2015).

1.3 Horse pendants

The information on a horse harness pendant that the book dates to the 13th -

The reference to a "Mediaeval winged belt fitting punctured by three rivet holes excavated in 2011 and must have once adorned a courtier's clothing" (p109) is somewhat misleading; for a start the excavators noted it was only 'probably medieval' (Brennan 2016, 52) not certainly so, but it is particularly unclear why it 'must' have adorned a courtier's clothing given that such bar mounts were frequently depicted on horse harness in medieval sculpture (eg Egan and Pritchard 2002, 209-

Even if it is from human clothing there is no apparent reason why it 'must' have belonged to a courtier, it could easily be from a belt (girdle) belonging to masons or other workmen employed on site or even one of the villagers, sumptuary laws from the time of Edward III mention girdles for ploughmen (Egan and Pritchard 2002, 35).

1.4 Summary regarding artefacts

With such basic and critical errors of dating and interpretation along with misleading statements about the majority of the included artefactual record (very few artefacts are actually discussed in this book which claims to be about archaeology), the reader would be entirely justified in having serious concerns about any of the conclusions that the book draws from such a flawed evidence base.

2. General archaeological and historical concepts and Terminology

These problems are, unfortunately, not just confined to the archaeology of Clipstone itself. The book makes basic and serious errors about medieval archaeology and history in general.

2.1 Medieval pottery

When discussing feasting, the book states that medieval diners "washed their hands in ewers" (p 109). Ewers are pouring vessels and the diners would have washed their hands in a basin into which water was poured from the ewer (Egan 2010, 158), and certainly not in the ewer itself.

In discussing what the author considers to be the small quantities of pottery found on the site the book declares that "Pottery was often preferred for serving up victuals as, unlike silver or pewter, it did not taint the taste of the food, although in the later Mediaeval period communal serving platters were used less as private dining became preferable. In this way food and dining became yet another method of social exclusion through the refinement of the palate" (p59).

The OED defines 'victual' as deriving from Old French victualis, from victus 'food' (https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/victual) and the Mirriam Webster dictionary indicates the term refers to "food useable by people" https://www.merriam-

The products of the medieval potter were predominantly jugs (for serving liquids), jars (for cooking and storage) and bowls (multiple uses but including dairying, cooking and food preparation) (McCarthy and Brooks 1988, 102-

Similarly, archaeological finds and documentary sources indicate that, at least by the post medieval period when it became widely available (McCarthy and Brooks 1988, 102) pewter was very much preferred by those who could afford it for the serving of food, including the large assemblage of pewter plates and dishes found aboard Henry VIII's warship the Mary Rose.

2.2 Medieval diet

The reader will find contradictions within the text. Regarding the medieval diet, for example, the book first states "the food and drink produced by the peasant community in the fields and tofts were [sic] based on cereals grown for use in ale, bread and pottage alongside vegetables such as peas, beans, onions and brassica. This was perhaps complimented by cheese, milk and honey. Meat was a rare commodity and the presence of animal bone may be equally indicative of their [sic] use in soups, stock and pottage as much as actual flesh consumption." (p148) but just one sentence later this is contradicted with: "The staple diet relied on fish, bacon, sausages and eggs with ... pottage together with a very gritty bread" (p148).

The site was first excavated by Phillip Rahtz in the 1950s, with some smaller scale excavation related to consolidation work on the ruin in the 1990s and with further consolidation work carried out in the 2000s. Research work began at the site in earnest, with geophysical survey and landscape analysis by Gaunt from 2009-

While the book is at times engaging and entertaining, it is unfortunate that the reader who picks up this book seeking to learn about the archaeology of this important royal site will likely come away, at best disappointed, and at worst seriously misled. Beyond this, ‘A Palace for our Kings’ has the potential to actually damage and harm the understanding of this nationally important medieval site in Sherwood Forest.

Consideration of previous work

General archaeological and historical concepts and Terminology

Interpretation of the built environment

1.2 Saxon and Medieval Pottery

1.4 Summary regarding artefacts

2. General archaeological and historical concepts

Project page links:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

The Sherwood Forest

National Nature Reserve Archaeology Survey

-

Long term Research at

King John’s Palace:

Ancient Royal Heart of Sherwood Forest

-

The Sherwood Forest Archaeology Training Fieldschool

-

“Scirwuda-

Ghost and Shadow woods of Sherwood Forest Project

-

Investigating Thynghowe Viking

Meeting Site

-

Searching for the

The Battle of Hatfield

-

-

Fieldswork at St Edwin’s Chapel

-

St Mary’s Norton-

-

Mapping Medieval Sherwood Forest

-

The Sherwood Forest LiDAR

Project

-

Warsop Old Hall

Archaeological Project

-

The Sherwood Villages Project:

Settlement Development in the Forest

-

-

-

Researching Edward IIs fortification at Clipstone Peel

-

-

-

-

The Cistercians of Rufford Project:

Settlement Development, Dynamics and Desertion.

-

Sherwood Forest Environmental Survey

-

World War II in Sherwood Forest -

-

World War I in Sherwood Forest -

-

About Medieval Sherwood Forest

-

Robin Hood and Sherwood Forest

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Project page links:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

The Sherwood Forest

National Nature Reserve Archaeology Survey

-

Long term Research at

King John’s Palace:

Ancient Royal Heart of Sherwood Forest

-

The Sherwood Forest Archaeology Training Fieldschool

-

“Scirwuda-

Ghost and Shadow woods of Sherwood Forest Project

-

Investigating Thynghowe Viking

Meeting Site

-

Searching for the

The Battle of Hatfield

-

-

Fieldswork at St Edwin’s Chapel

-

St Mary’s Norton-

-

Mapping Medieval Sherwood Forest

-

The Sherwood Forest LiDAR

Project

-

Warsop Old Hall

Archaeological Project

-

The Sherwood Villages Project:

Settlement Development in the Forest

-

-

-

Researching Edward IIs fortification at Clipstone Peel

-

-

-

-

The Cistercians of Rufford Project:

Settlement Development, Dynamics and Desertion.

-

Sherwood Forest Environmental Survey

-

World War II in Sherwood Forest -

-

World War I in Sherwood Forest -

-

About Medieval Sherwood Forest

-

Robin Hood and Sherwood Forest

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Community Archaeology in Derbyshire

Community Archaeology in Leicestershire

Community Archaeology Nottinghamshire, Excavation, Research, Volunteering, Community Archaeology Derbyshire, Training, Social, Learning, Community Archaeology Leicestershire, Heritage, Involvement, Belonging, Knowledge sharing, Community Archaeology Lincolnshire, Topographic Survey, Talks and Presentations, Outreach, Archaeology Projects , Open Days, Schools, Finds Processing, Day Schools, Field Schools, Young People, Archaeology and History of Sherwood Forest, Pottery Research, Medieval, Roman, Prehistoric, Community Interest Company, Community Archaeology Nottinghamshire.

Community Archaeology in Nottinghamshire

Community Archaeology East Midlands

Community Archaeology in Lincolnshire

Community Archaeology in Yorkshire

Mercian Archaeological Services CIC

Specialists in Community Archaeology, Public Involvement, Research & Training

© Mercian Archaeological Services CIC 2024. Registered Business No. 08347842. All Rights Reserved.

The Future of Sherwood’s Past

Community Archaeology Nottinghamshire, Community Archaeology Derbyshire, Community Archaeology Leicestershire, Community Archaeology East Midlands, Mercian Archaeological Services Community Archaeology for Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire, Sherwood Forest, Leicestershire and the East Midlands. Community Archaeology Nottinghamshire, Community Archaeology East Midlands, Community Archaeology Leicestershire. Archaeological

Book Reviews -